Industry experts and artists have begun to question the environmental impact of nonfungible tokens, also known as NFTs, due to the growing awareness of the global ecological damage and climate change caused by technological progress.

In spite of the meteoric rise in popularity of these kinds of digital assets over the course of the past year, it is far too soon to collect reliable data on which to base an evaluation of the environmental risks posed by NFTs.

Even though we are starting to see some numbers, none of this information has been validated by specialists from the outside world and, therefore, cannot be trusted just yet.

The technology behind blockchain, which is based on nonfungible tokens, confers exclusivity and unrepeatability on digital assets.

The creation of photos, videos, and musical works can be duplicated digitally in an infinite number of ways; however, blockchain smart contracts ensure that a single piece of artwork or video, for example, is the only representation that exists of that item.

Additionally, the technology enables the user to conduct business in a trustless setting, which eliminates the requirement for any third parties to validate the legitimacy of the transactions.

These factors contribute to the value of non-publicly traded companies (NFTs) and are the driving force behind their growth in a variety of industries, particularly the arts.

The artists’ environmental impact is also becoming a primary concern for them. As a result, they are taking a variety of steps to combat climate change and reduce the carbon footprint that NFT leaves behind.

Are NFTs bad for the environment?

The digital artist Beeple, whose piece “Everydays: The First 5000 Days” was recently the subject of a record-breaking auction at Christie’s, is a proponent of a more environmentally friendly future for NFTs and has made a commitment that all of his future artwork will be carbon neutral.

He believes that if he invested some of his money in renewable energy, projects that conserve the environment, and the development of technology that reduces CO2 emissions, he could compensate for the emissions that his NFTs cause.

Beeple could determine, with the assistance of a straightforward tool like Offsetra that is designed to assist artists in calculating their footprint, that in order to offset the emissions from one of his collections, he needs to make a contribution of $5,000 to offset his environmental impact.

Beeple and a number of other prominent artists came to the conclusion that they should work together to sell carbon-free NFTs and raise money for Open Earth Foundation.

Through the use of art and education, the charitable organization promotes the concept of sustainable development as well as solidarity.

These particular funds were allocated to the development of blockchain technology for the purpose of establishing climate accountability.

Each participating artist and artwork was awarded sixty carbon offsets, representing a commitment to reduce their NFT-related carbon footprint and produce a climate impact that is overall positive.

What is the carbon footprint of an NFT?

Although it is difficult to determine the ecological cost of crypto art precisely, different estimates can provide us with an idea of the carbon footprint of an NFT.

For instance, the weight of a single-edition artwork on Ethereum is equal to 100 kilograms of CO2 and 220 pours, which is the same as flying for one hour.

Digital artist Memo Akten conducted an analysis of approximately 18,000 NFTs and discovered that the carbon footprint of the average NFT is equivalent to more than a month’s worth of electricity usage for the typical person living in the European Union.

The effect of technology on the natural world takes us all the way back to the beginning of the industrial revolution when technological progress made the development of new manufacturing processes possible.

Such progress also marked the rise of environmental damage, which, closer to our days, has found particular environmental hazards in data centres and crypto mining.

The remote storing, processing or distribution of large amounts of data is performed by companies such as Google and Amazon on what is known as a data centre, which is an infrastructure consisting of networked computers.

When we send an email or a message through WhatsApp, the information travels through one of these data centres, which consumes a significant amount of power to function effectively and keep the equipment at a comfortable temperature.

One percent of the world’s total energy demand is accounted for by data centres. A possible increase in emissions of up to 3.2 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent can be attributed to the increased use of the internet that occurred during the pandemic.

Consider that one metric ton is roughly equivalent to the weight of a car or the amount of CO2 that would be produced if you drove from San Francisco to Atlanta. This will help you understand the implications of such an evaluation.

Every single digital process results in energy consumption. For example, a research report published by the NASDAQ estimates that the global banking industry uses approximately 263,72 Terawatt hours of electricity every single year.

On the other hand, Bitcoin (BTC), which is not only the most widely used blockchain and cryptocurrency but also the one that requires the most energy to operate, consumes a little less than half of that amount.

The mining of cryptocurrencies is an additional cause for concern regarding their effects on the environment. The effect that it has is comparable to that of data centres.

Even though more data has become available over the past few years, particularly in mining Bitcoin, it is not yet possible to estimate the actual environmental impact of blockchain technology as a whole because it depends on various measures, causes, and processes.

For example, there is a substantial distinction between the blockchain technology that is supported by a proof-of-work (PoW) consensus algorithm and the proof-of-stake consensus algorithm (PoS). A little further down in the article, we’ll take a closer look at the distinction between the two.

The vast majority of non-fungible tokens (NFTs) are transacted and stored in the Ethereum network via the proof-of-work mining procedure.

PoW is the type of consensus algorithm that requires the most energy consumption. This is where the discussion among climate experts about the effects of NFTs on the environment begins.

Ethereum is the second most stable and reliable cryptocurrency after Bitcoin, which is one of the reasons why digital artists choose it for the sale of their digital artwork.

Furthermore, it was designed to transact data beyond cryptocurrency transactions using smart contracts, making it an appealing platform for various usages other than cryptocurrency transactions.

How harmful are the NFTs stored on Ethereum?

Multiple studies have been conducted on cryptocurrency’s energy consumption, but they all report distinct numbers. It is reasonable to estimate that between 30 and 70 percent of cryptocurrency mining is powered by renewable energy, but this is an imprecise and all-encompassing estimation that is not specifically aimed at Ethereum.

Mining for Ethereum utilizes significantly less power than mining for Bitcoin does. According to the most recent and reliable estimate, which was conducted in 2018, it was determined that the platform consumes approximately the same amount of electricity as Iceland.

It has been estimated that Ethereum uses approximately 44.94 terawatt-hours of electrical energy on an annual basis. This is roughly equivalent to the amount of power used annually by nations such as Qatar and Hungary.

It is equivalent to the carbon footprint of Sudan, which is approximately 21,35 metric tons, as the amount of carbon dioxide it emits into the atmosphere.

Every Ethereum transaction is carried out using Ether (ETH) as gas, which is then transparently recorded on the blockchain. The gas percentage varies depending on the amount of transaction data, as does the emission impact of the transaction.

NFTs are digital items that require a large amount of data due to the multiple transactions involved in creating them. These transactions include minting, bidding, trading, and the transfer of ownership.

Because of the transparency of the transactions, it is possible to conduct an easy analysis of an NFT’s footprint.

The question that is being discussed is whether or not Ethereum mining would produce emissions regardless of whether or not NFTs had a significant impact on the process.

Even though Ethereum mining was already in operation and contributing to environmental pollution before NFTs were developed, the energy requirements of NFTs are unquestionably higher than those of a standard money transfer transaction on Ethereum.

As an analogy, we could consider the fact that an airplane or train will continue to operate regardless of the number of passengers on board.

On the other hand, if a growing number of people generate, trade, and store NFTs, then a growing number of energy-intensive transactions will need to be generated, which will lead to an increase in the amount of carbon emissions.

To get to the heart of the matter, determining how much of an impact NFTs are having on Ethereum transactions and how much damage they are doing to the environment is not a simple matter.

Proof-of-work vs. proof-of-stake energy consumption

NFT investors are now able to buy, sell, or store digital assets without the need for a third party, thanks to the technology behind blockchain.

However, in the present day, in order to successfully complete these transactions, a certain level of technological savvy is required.

Because of this, artists who are looking for a streamlined and uncomplicated experience often gravitate toward using online marketplaces such as Opensea or Rarible.

However, these and the vast majority of other marketplaces are built on Ethereum’s proof-of-work blockchain, which is highly inefficient with regard to the use of energy and has resulted in high fees ever since NFTs began populating the platform.

Alternatives to proof-of-work based on the proof-of-stake consensus algorithm have emerged as more sustainable forms of blockchain technology. Proof-of-stake blockchains consume 99% less energy than proof-of-work blockchains and are associated with more environmentally friendly NFTs.

On the other hand, these blockchains have a reputation for being riskier than others due to the fact that they are typically less established on the market and, therefore, more prone to being hacked, for instance.

This is the primary reason why art buyers who want to ensure that their artworks won’t vanish or won’t be supported one day find these networks to be less attractive than others. Art buyers want to make sure their investments won’t be lost.

In addition, these platforms do not yet have a significant volume compared to their less sustainable counterparts, making it more difficult for artists to buy or sell items in a timely manner.

It is possible that, in the not-too-distant future, there will be a surge in the use of these platforms and an increase in the development of more eco-friendly and transparent marketplaces. This surge may occur as more artists become increasingly aware of other, more energy-efficient alternatives.

To name a few of the most well-known chains that utilize proof-of-stake, we can mention Algorand, Tezos, Polkadot, and Hedera Hashgraph.

Several years ago, Ethereum made the announcement that the Ethereum 2.0 upgrade would involve a transition to a proof-of-stake consensus mechanism.

Artists are keeping their fingers crossed that Ethereum’s energy consumption will soon drop by a significant amount as a result of this change.

Other non-fungible token platforms, such as Flow, already fully utilize the technology of private blockchains and operate in full capacity.

On the other hand, private blockchains are highly centralized and deviate from the actual blockchain concept. The latter suggests that the decentralized system does not require the intervention and trust of an intermediary.

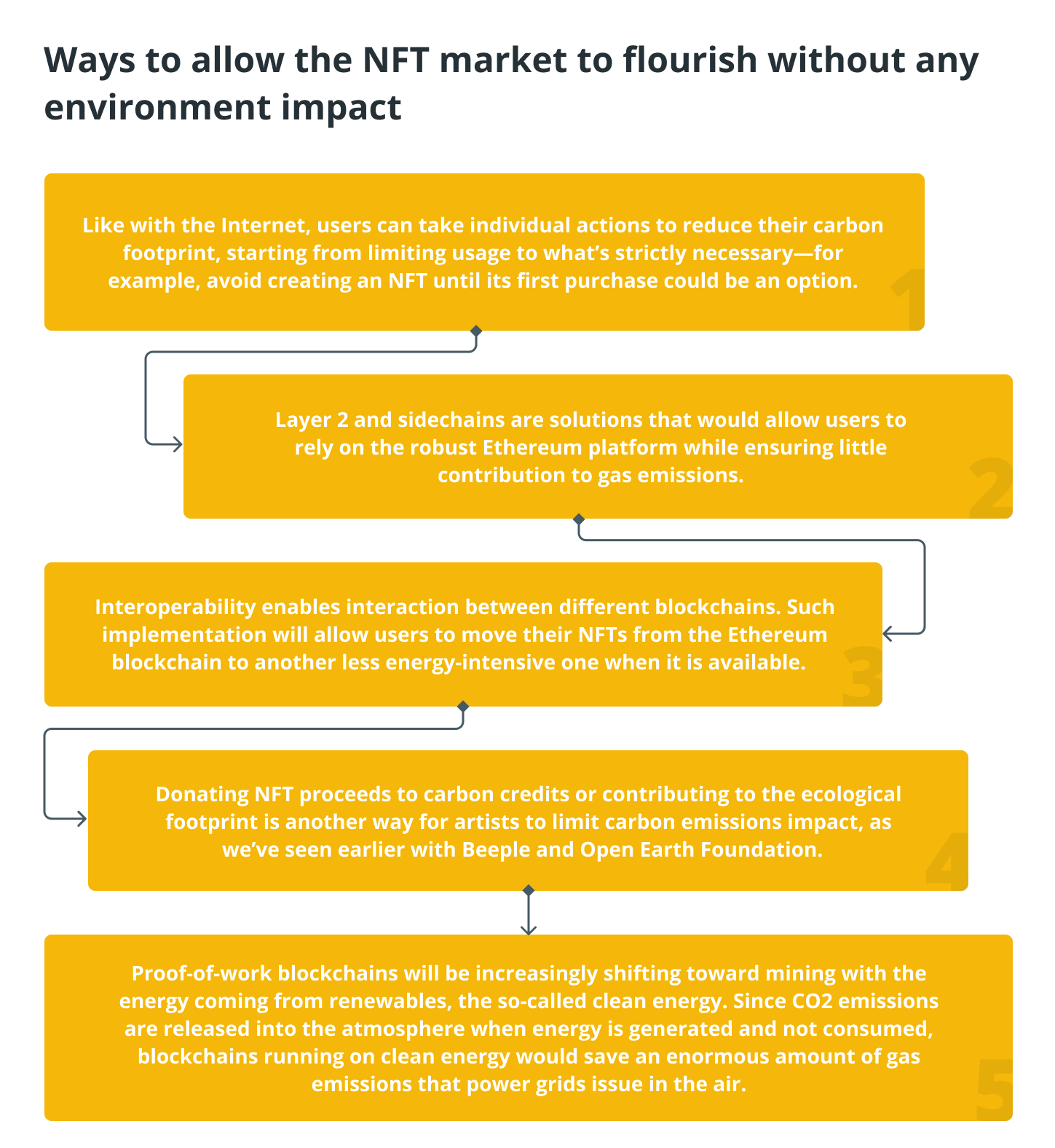

What other steps can be taken to improve NFTs’ carbon footprint?

We mentioned that Ethereum could move to a consensus algorithm known as proof-of-stake, which would make it significantly less dependent on the consumption of energy.

However, the development team for the platform has been maintaining it for years. Still, the process has never materialized so far, raising legitimate doubts about the claimed achievement.

By constructing systems on layer two, which would be built on top of the existing blockchain, developers of Ethereum could cut carbon emissions and cut costs.

Because these systems allow for all transactions to take place off-chain, a significant amount of energy could be saved through them. This would mean that the energy-inefficient proof-of-work mechanism could eventually be phased out.

For instance, Bitcoin’s Lightning Network is a protocol that was built on layer two of the blockchain, and it is now considered Bitcoin’s payment system. This was accomplished by using a proof-of-work consensus mechanism.

Due to the fact that it does not rely on the proof-of-work consensus function of the base chain, it is both scalable and friendly to the environment.

Using the process of the Lightning Network as an example, individuals or organizations that want to trade NFTs could open a second layer channel to virtually make unlimited trades until they are ready to settle the total transactions back on the PoW blockchain base layer, also known as layer one.

This would be done in a manner similar to how the Lightning Network process works.

In this way, rather than flooding the base blockchain with an unlimited number of transactions, only the final result will be time-stamped on the blockchain. This will prevent an extremely large number of data-intensive transactions from being completed, saving a significant amount of energy.

The following are some of the additional steps that can be taken to mitigate the impact of the growth of the NFT market on the surrounding environment while still allowing it to thrive.

Having said that, renewable sources of energy have not yet completely replaced the existing infrastructure of power generators, and it would be unwise to rely solely on these sources.

Climate change researchers, as well as skeptics of blockchain and cryptocurrencies, argue that the energy generated by renewable sources is still very difficult to come by. As a result, it should be saved for more pressing uses such as lighting and heating.